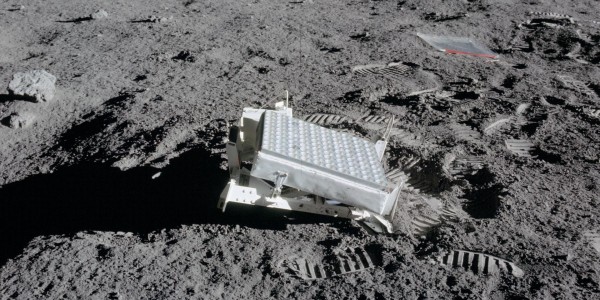

Nearly in a panic, Michael Collins called out to his crewmates, “Keep talking to me, guys!” The lunar module with Armstrong and Aldrin aboard had just separated from the command module to fly down to the surface of the moon. Collins, the third astronaut on the Apollo 11 mission, had to wait in the Columbia for the other two to return. When his crewmates were stepping onto the moon before the eyes of the world, Collins was already dipping behind the dark side of the moon. For hours there in the Columbia, he was the loneliest person in history. “I am alone now, truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life,” he noted, while also feeling a sense of great joy.

Michael Collins is often called the forgotten astronaut of the first lunar mission. Even Richard Nixon overlooked him: The president sent greetings to the first two people on the moon, but not to the third man on the mission. The success of Apollo 11 is due also to Collins, who was not only selfless and unpretentious, but also extremely meticulous.

The weakest link in the chain?

Michael Collins was born in Rome, Italy, on October 31, 1930, the son of high-ranking US Army officer. Like his future crewmate Aldrin, Collins studied at the US Military Academy at West Point. Then he took the traditional path to NASA: fighter pilot, later test pilot, and reaching his goal in 1963. In 1966 he became the first astronaut to capture an obsolete satellite during a spacewalk. All told, he spent more than 11 days in space.

One month after returning from the Apollo 11 mission, Michael Collins wrote in LIFE magazine: “Any flight like this is an extremely long, fragile daisy chain of events.” He was well aware that “any chain as long and as tenuous as this had to have a weak link. Believe me, I spent a lot of time before the flight worrying about that link. Could I be it?” He waited for hours in the command module, “sweating like a nervous bride,” to hear from his crewmates that the mission was going according to plan. He felt he would be “marked for life” if he had to return to Earth alone.